Competency to Stand Trial and Standard of Proof

This court has found, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the defendant is, in fact, a pirate.

In 1989, Byron Cooper broke into a home and was robbing it, when the 86 year-old owner confronted him. Mr. Cooper attacked and killed the owner of the house. The evidence against Mr. Cooper was solid, and the prosecution was going to have little difficulty proving him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The problem with Mr. Cooper's case, however, was that he had a severe mental illness. He was psychotic, and his psychosis caused him to be terrified of his defense attorney. On at least one occasion, he attempted to run out of the courtroom when he saw his attorney, not because he was trying to escape but because he delusionally thought his attorney was evil. Mr. Cooper also refused to wear street clothes in court because they "burned" his skin. He was also fond of curling up in the fetal position on the floor of the courtroom and talking to himself.

Mr. Cooper's defense attorney claimed he was incompetent to stand trial, and Mr. Cooper went through a number of competency evaluations. He also spent time in the Oklahoma State Hospital where he received restoration to competency treatment.

Just prior to his trial, Mr. Cooper's attorney again raised the issue of competency. He went through another evaluation, and the psychologist's opinion was that he was, in fact, incompetent. However, the judge ruled that the defense had not proven Mr. Cooper's incompetency with clear and convincing evidence, thus deciding Mr. Cooper was competent and ordering him to face trial. He was quickly found guilty and was sentenced to death.

Let's back up for a minute: in the United States, we take our court system seriously. Very seriously. The judiciary is enshrined in the US Constitution, and beyond that, five of the ten Amendments in the Bill of Rights deal with protecting individuals from what could otherwise become a tyrannical court system.

Out of this desire to protect an individual's liberty arose the concept of Competency to Stand Trial. In order for a person to be able to exercise his/her Constitutional Rights, he/she must be able to understand those rights, make rational decisions regarding those rights, and work with his/her attorney to assist in exercising those rights. More specifically, an incompetent person who faced trial would be deprived of Due Process (Fourteenth Amendment).

When a person claims to be incompetent, the defense has the burden of proving the defendant is actually incompetent. The defense attorney must present evidence that the person has a mental problem that affects his/her ability to rationally and factually understand the proceedings and to cooperate with counsel. This is typically done through competency evaluations conducted by forensic psychologists or psychiatrists.

But let's back up a little more and discuss Burden of Proof: This is a legal and philosophical concept describing who has the obligation to convince the factfinder to change his/her mind regarding a particular situation. For a competency hearing, the judge is supposed to assume the defendant is competent unless the defense attorney can prove the defendant is incompetent. Thus, the burden is on the defense in this case.

There are several levels of proof required for someone in court to meet his/her "burden." They are as follows:

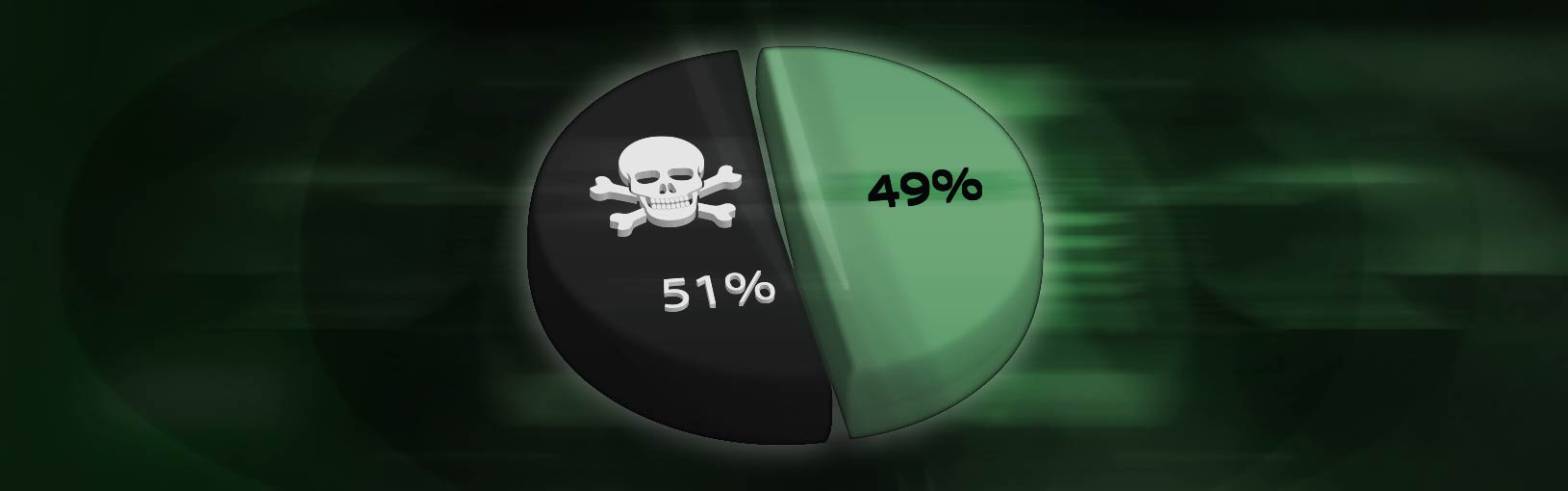

1. Preponderance Of Evidence: The issue is more likely to be true than not true.

2. Clear And Convincing: The issue is much more probably true than not true, and the factfinder must be strongly convinced.

3. Beyond A Reasonable Doubt: This is the highest level of proof required in criminal cases. Although it does not require the factfinder to have absolute certainty, he/she must come to the conclusion that there is no reasonable or plausible explanation for events other than what is being argued.

So, let's get back to Mr. Cooper's case. The judge ruled him to be competent because the defense did not prove his incompetence by clear and convincing evidence. He then went to trial, was found guilty, and was sentenced to death.

His defense attorney appealed this decision, claiming Mr. Cooper's Due Process Rights had been violated. An appeals court affirmed the lower court decision and upheld the conviction and sentence. The defense then appealed to the US Supreme Court. In 1996, the Court issued an unusual unanimous ruling on this case: They decided Mr. Cooper's Due Process Rights had, in fact, been violated. They stated the lower court used the wrong standard with clear and convincing, and instead should have heard the case using the preponderance of evidence standard.

The US Supreme Court claimed the higher standard "imposed a significant risk of an erroneous determination that the accused was competent, and such determination threatened a fundamental component of the criminal justice system...the accused's fundamental right to be tried only while competent outweighed the state's interest in the efficient operation of its criminal justice system."

The Court reversed Mr. Cooper's conviction and sentence and remanded the case back to the lower court to deal with the competency issue using the preponderance of evidence standard.

Due to Cooper v. Oklahoma, all states are now required to use the preponderance of evidence standard when determining whether an individual is competent to stand trial.